The buzzwords surrounding technology in education continue to proliferate. Recently, one acronym has clearly emerged as the most talked about, STEM. In fact, President Obama just announced on March 23, $240 million in private-sector pledges to fund STEM education programs through his “Educate to Innovate” program.

Along with many other trends in education, STEM’s appeal lies in the a belief that it will prepare students for an area of the national economy with many open positions to fill. STEM (Science/Technology/Engineering/Mathematics) has become a catch-all for terms such as “innovation,” “design,” “coding” and “maker” and one of the great leaps of STEM is the recognition that singular subject courses are limiting. The combination of several traditional academic areas leads to better understanding of each of these topics as a whole.

So popular has the STEM acronym become that we now see efforts expand it to properly include other topics:

STEM+C (adding Computer Science)

STEAM (A for Arts, to include a design component)

STEMx (x as place holder to represent a host of related topics)

In his Huffington Post opinion piece Eliminate the Silos, John M. Eger, Director of the Creative Economy Initiative at San Diego State University points out that this fusion of subjects should only be the beginning “STEM and STEAM concepts are really “placeholders” for something else that needs to be done in K-12 education and the universities: elimination of the silos and a renewed focus on interdisciplinary learning.

Yet at what point does the desire to fall in with trendy branding lose sight of the substantive goal: to teach analytical thinking? My work toward developing a new Upper School course on called Design Thinking, Applied Programming and Fabrication, has provoked me to think a great deal about the the meaning of STEM curricula. The trend toward packaging all learning as extensions of a STEM framework seems to negate the importance of Liberal Arts. It’s a perspective we at Hackley cannot embrace.

Other education experts are also pushing back against this trend while pushing for a re-emphasis on the Liberal Arts. Among these Michael Roth, President of Wesleyan University, whose book Beyond the University: Why Liberal Education Matters explores this challenge. In an interview Roth stated: “The problem is we have this polarized discourse around education, where people think that somehow a utilitarian, marketplace-oriented education has to take place at the expense of a broad and contextual one” In a New York Times op-ed piece, College’s Priceless Value, author of the book, Where You Go is Not Who You Will Be, Frank Bruni writes: “And it’s dangerous to forget that in a democracy, college isn’t just about making better engineers but about making better citizens, ones whose eyes have been opened to the sweep of history and the spectrum of civilizations.” At the The Institute of International Education, Yong Zhao, author of Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Dragon, made the point that the Chinese government, after many years of emphasizing standardized testing and content based learning, is now looking at the western liberal arts approach. And just recently, Fareed Zakaria released In Defense of a Liberal Education. In his Washington Post op-ed piece coinciding with the book’s release, Why America’s obsession with STEM education is dangerous, he writes, “Critical thinking is, in the end, the only way to protect American jobs.”

Why do educational trends insist on dividing school subject areas into disparate “STEM” and “non-STEM” buckets, and what does this do to our ability to teach critical thinking? Charles Fadel, Chairman of the Center for Curriculum Redesign and keynote speaker at a recent tech conference I attended, asks “When did Science and Mathematics stop being part of the Liberal Arts?” Can a liberal arts education create a context where students can improve their STEM skills?

While new and trendy buzzwords frequently emerge and grab headlines, the best practices underlying the buzzwords recognize the essential place of critical thinking. The Code movement, for example, has also dominated discourse in recent months, yet is is nothing more or less than what Hackley has been doing for years within a computer science program built on a foundation of critical thinking and problem solving.The problem-solving process includes : analysis (define the problem, break down into subproblems, determine input, determine output), creation of Plan, testing the Plan, translation or the plan to code, and testing of the translation. A bulk of the time in the process is spent on analysis.

The established Hackley computer science problem solving process also encompaasses what the STEM education world now calls “Design Thinking.” Don Buckley outlines the process as follows:

- Define the Problem

- Research the Problem

- Analyse & Redefine the Problem

- Ideate Solutions

- Prototype the Solutions

- Refine the Solutions

- Repeat as Needed

- Choose the Solution

- Implement the Solution

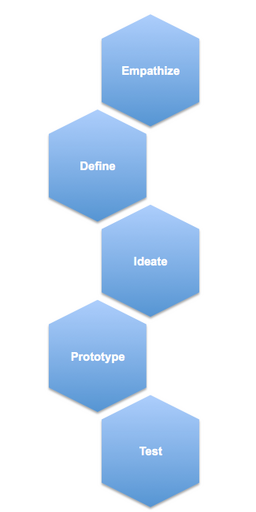

My work within Hackley’s own professional development program revealed something interesting: Design Thinking actually introduces an additional component to the process listed above. Maureen Carroll, Ph.D., from Line Design describes an approach from Hasso Plattner Institute of Design commonly known as the “d.school” — the home of Design Thinking, first developed by David Kelley— that emphasizes empathy as the starting point, followed by “define,” “ideate,” “prototype,” and “test.”

The “empathize” component seems at first glance to have little to do with proper problem solving. The computer science perspective might argue that a problem’s best solution is based on factors such efficiency and lack of ambiguity. Yet consider this: ultimately all kinds of people are going to use the code you write or the contraption you engineer. Executing that design, therefore, requires you to understand your audience, to empathize with their needs. Empathy, therefore, is an essential aspect of problem solving: it enables development of solutions that anticipate user input.

Earlier this spring, Hackley parent and president of Greenlight Capital, David Einhorn, came to speak at Hackley on philanthropy; empathy was major subject of his talk, which drove home the importance of empathy in problem solving. Mr Einhorn stated: “It’s all a matter of perspective. What’s difficult is to understand why the person on the other side is doing what he’s doing. Being able to consider the world through someone else’s eyes is the essence of empathy, and that’s what it’s going to take for us to really get along.”

How, then, do we teach students this ability to consider the world through someone else’s eyes to most effectively begin the process of Design Thinking/Problem Solving? I believe we can do this by providing them context from a range of subjects. In his Chronicle of Higher Education article Is Design Thinking the New Liberal Arts?, Peter N. Miller writes “What the liberal arts–or humanities–give us are the experiences of those who have come before us to add to our own. these surrogate experiences help to live well in the world”

What does this do to our acronym? Perhaps STEM becomes SCHLAEM:

Science

Computer Science

History

Language

Arts

English

Mathematics

Exposure to each of these subjects is essential to gaining understanding of the others. In a school context that explores them all, students constantly employ the critical thinking and design thinking/problem solving skills that lead to lifelong learning.

“Technology alone is not enough… it’s technology married with liberal arts, married with humanities, that yield the results that make our hearts sing” – Steve Jobs, iPad2 intro speech, March 2011

Another fantastic article Jed! Thanks!