Hello! Welcome to the 2022 Arrow – Hackley Middle School’s Arts & Literature Magazine. Stay tuned for more posts to come over the next few weeks and then keep an eye out for the hardcopy, published version coming soon.

Let’s mix it up a bit with some writing and some visuals!

Stolen Freedom

“6 of Ways of Seeing animal cruelty”

by: Evelyn W. ’28

1.

His body is dead,

But he is still here

His horns are gone just like he is.

Another flower has withered today.

2.

He is a poacher.

He stares down at his new victim,

his face remains flat,

He is a monster.

3.

He is scared,

a mouse in a cat game.

He can only watch,

and wonder if he will be next.

The freedom of the forest smelled sweet,

But the forest has turned into a jail.

A jail that tastes bitter.

4.

He is empathetic,

Helping where he can.

It’ll never be enough.

His anger is sharp and melancholy.

5.

He is a bystander,

He likes the decorations of tusks and horns.

He will not do anything,

He doesn’t care.

6.

He is alone,

The animals are gone.

He is a habitat that is empty,

A soul with no essence.

Evelyn W. ’28

Lonely Colorado

by: Charlotte F. ’28

I am bumpy like cobblestone,

mysterious like a haunted house.

I am a mountain.

My hair is white.

My head is very cold.

Whenever people go up to my hair,

they always bring serious gear.

My friends keep telling me,

that I am too tall

so I tell them

that they are just too small.

I am only 14,000 feet.

I know mountains whose hair

touches space.

My friends say

they wish to be up here.

I wish I was down there.

I am lonely,

No one dares

To climb up here.

I never see anyone.

I am covered with animals,

such as snakes

waiting to kill.

Every day, I watch the clouds,

that is all I can see.

At night,

the clouds disappear.

I stare at the little ranch.

I feel as though

it is my only true friend.

I can’t tell with the horses.

Some love me;

some hate me.

They love what I give them-

rivers,

food,

space.

I am dangerous.

I have poison,

cliffs,

steep hills,

hills where you can not see beyond,

trees so tall and pointed they can poke your eye out.

I am waiting

for that one person,

someone who dares to climb up here.

I have wonders as well:

rivers filled with fish,

hikes that give you a new perspective,

animals,

glaciers that will not be here for too long.

I have some downsides,

but I am also filled with joy.

I have all the best weather –

hot like a nice summer day,

cold like a day in Greenland,

crispy like a nice fall day.

You choose.

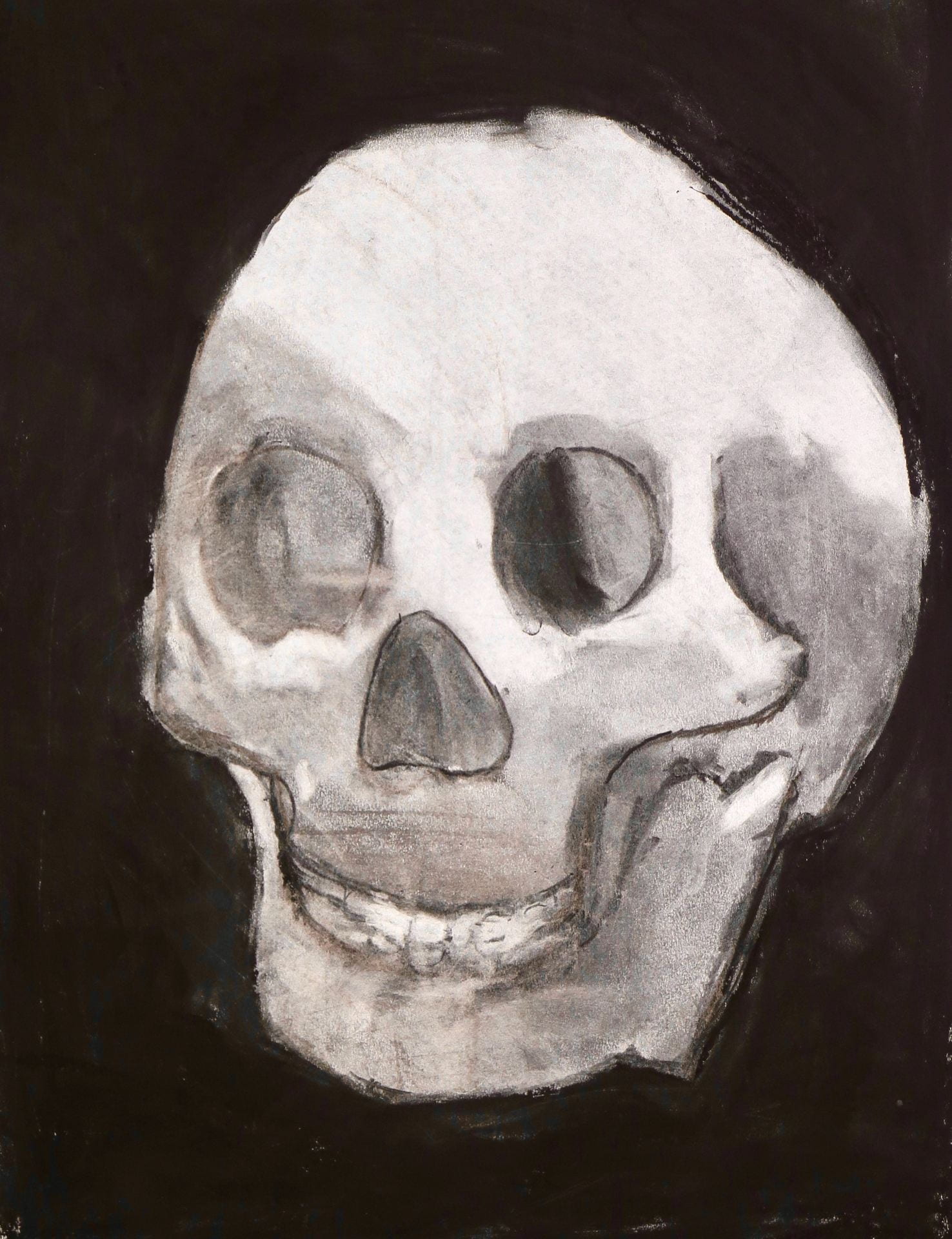

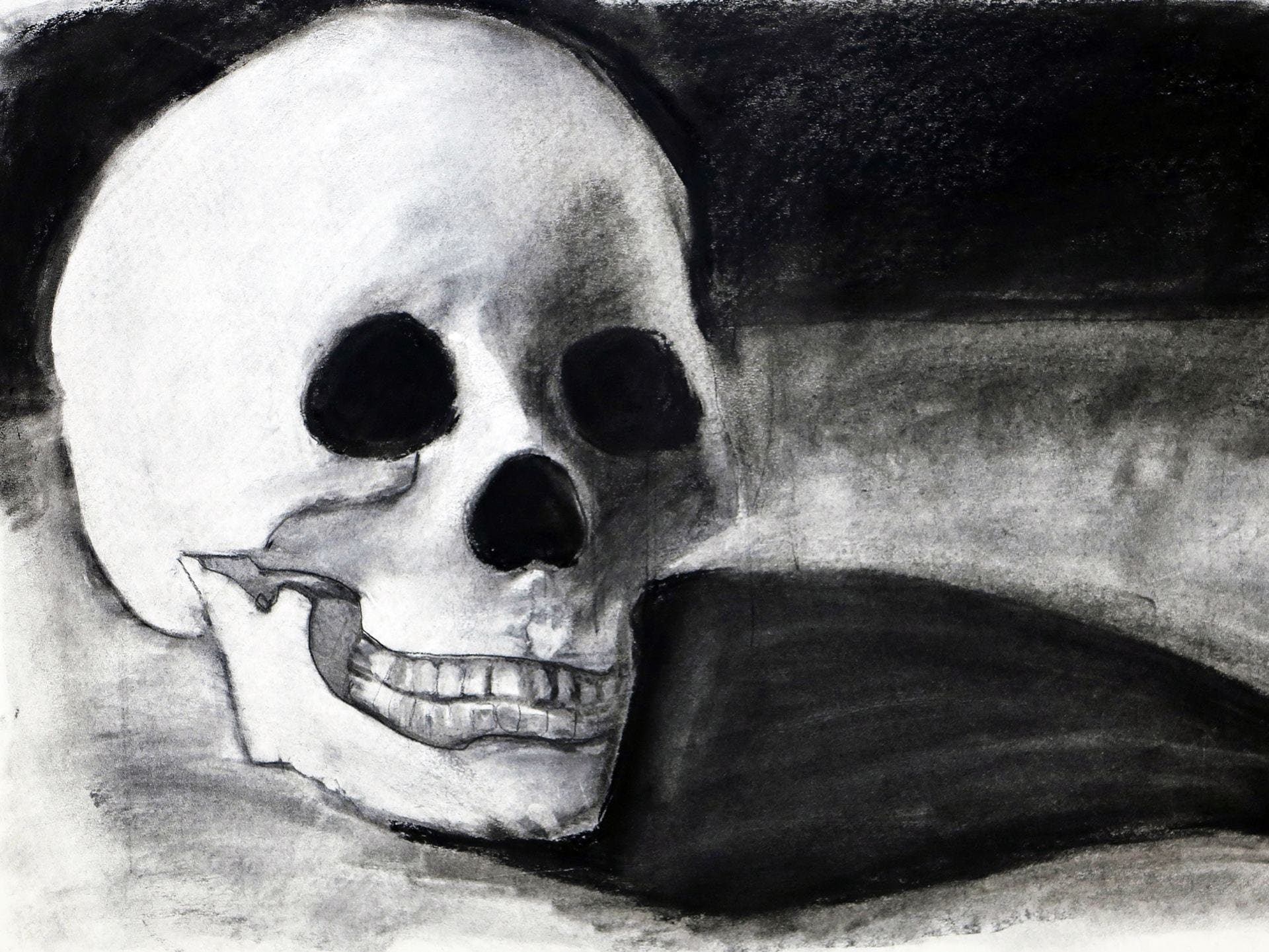

Theo A. ’27

Theme for Going to Bed

by: Charlie N. ’27

My Dad told me to go to bed.

“Go to bed”, what?

I’m not tired; I am still in a game.

I am on the phone. What bed?

It’s too early. Please, ten more minutes.

Am I tired? Or do I just want to stay up?

I should go to sleep, but do I?

No, I don’t of course not, but

I should.

Kayla R. ’28

The King

Sarah S. ’28

Light glints off metal.

I will win this.

A graceful dance,

but in the end, there is only one winner.

I feel the air bowing before me, fleeing,

not daring to interfere.

I cut them all down.

Blade meets blade,

A struggle of force and strength.

The white blur of my opponent catches my eye as I duck and dodge,

attack and retreat,

parry and disengage.

This is all a game to me.

I lunge –

the satisfying THUNK of hitting my opponent rewards me.

A buzzer sounds;

I am the champion.

My owner sheathes me.

I am the king,

The king of fencing.

I rule every fight.

Charlie W. ’29

Tapping Maple Trees

by Elleana D. ’28

The fall leaves change from green, to red, orange, and yellow.

Each day, they got older and darker.

The trees were as tall as a house.

During the fall, I recall my favorite memory,

tapping maple trees.

I hear the crunch as people walk over the crisp leaves

that have fallen from the aging trees.

My dad hammers the spindle into the tree,

and I remember the overwhelming clink as he hits it.

The sweet aroma of syrup fills the air.

I remember the beautiful fresh autumn flare.

The sap is glue.

As I touch the trees, it sticks to my fingers.

The bucket feels cool and heavy as I help lift it onto the spindle.

We walk away, and I look back at the trees.

The weeks drag on like years.

I cannot wait to come back to see

what treasure has flowed into my silver bucket.

Mia S. ’28

The Last Tree

by: Heidi C. ’28

I heard it,

Mechanical buzzing,

I felt it,

A rumble like an earthquake

And then I saw it,

The monster,

Giant cart-like car,

Monster truck wheels,

And saws, huge, spinning saws

It got closer and closer,

As the buzzing intensified,

As the rumbling got louder.

I heard a grinding sound,

Wood bits flying everywhere,

As my friend yelled,

“Help!”

The realization came to me,

It stung.

I could not do anything to help,

Nor could the animals

I couldn’t move.

All I could do was watch and sob,

As my dear friend collapsed,

And as he fell to the ground,

His leaves fluttered in the air.

And then all of the others began to

Collapse with him,

Fallen leaves fluttering,

Wood bits flying,

I waited for my turn,

Hopeless,

Heartbroken.

The man operating the machine yelled,

“That’s enough lumber!”

And that dreadful machine

Stopped in my face.

At this point, I prefer to be chopped down,

Along with my friends,

Along with my family,

But they left me alive,

For what?

I was furious.

Why?

Why did my friends get chopped down?

For paper?

For napkins?

Such insignificant things,

Compared to my friends,

My friends and I

Have kept people alive,

Providing oxygen

For all living things,

And why,

Why did I have to remain here,

All alone,

For so many animals

Rushed to me,

For shelter,

For comfort,

As their homes

Were destroyed.

John Pierre N. ’26

Fall Poem

by: Isabelle G. ’28

Every year when fall comes around and the leaves change color,

I am reminded of my favorite fall memory:

hiking in the woods

catching the falling leaves

feeling the smooth yet brittle leaves crumble in your hands

and the smooth veins of living ones

the crunching of the leaves under my feet

the rustling trees in the wind

When you look up, the blue sky is hidden by the bright leaves.

So many colors

red

orange

yellow

green and brown,

so many more than I can count.

The crisp smell of apples and cinnamon,

a drifting scent of maple trees and syrup linger,

warm and cozy.

A bowl of chicken soup

makes me feel right at home in the chilly weather.

The aftertaste lingering in my mouth

makes me feel snug in my layers of jackets and sweaters.

Luke T. ’27

Love Letter to Pizza

by: Jack M. ’28

To my cheesy, wonderful Roma pepperoni pizza,

I feel so much love for you today that I had to stop and express my feelings for you. I love you so much, and I know it is strange for a 12-year-old boy to be declaring his love for a piece of pizza, but this feels so natural to me. I wish our relationship could last forever but unfortunately, you have an expiration date, and you will get moldy and gross over time.

As soon as my lips touched your perfectly melted cheese, it was love at first touch. It was just a normal summer evening, but from that moment on, my life changed forever.

I love your amazing combination of hot cheese melting in my mouth when I take a bite. The pepperoni gives a perfect touch to your perfectly sized crust, made from the finest bread in all of Westchester County. I just wish I could feel your flavors burst in my mouth just once more. Your pepperoni blows my mind in thirty-five different directions. You are devastatingly attractive, and I wish our love would go on forever. I am yearning for the day that my bank account can support a lifetime supply of you. I will see you soon my love.

Forever yours,

Jack M.

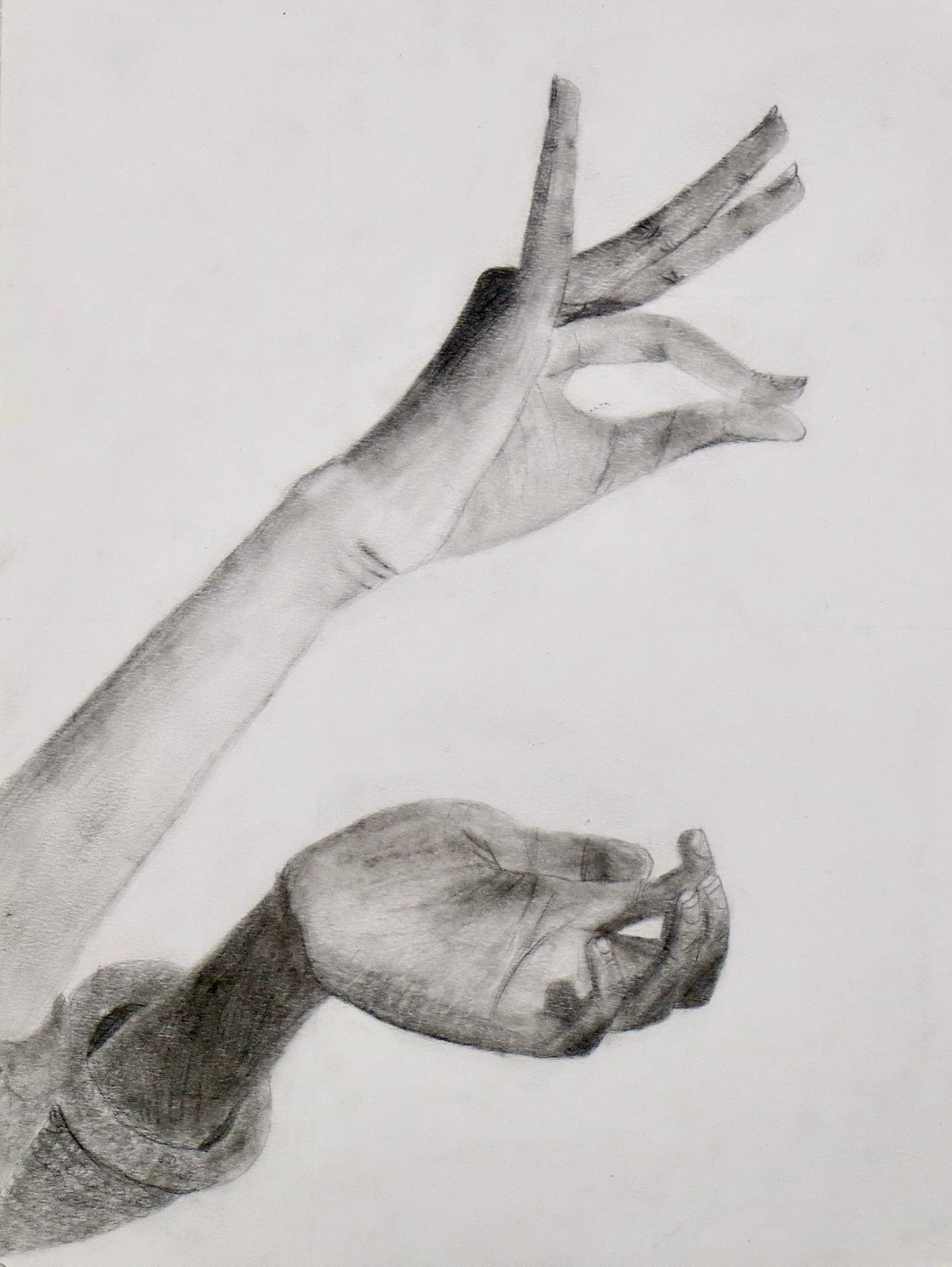

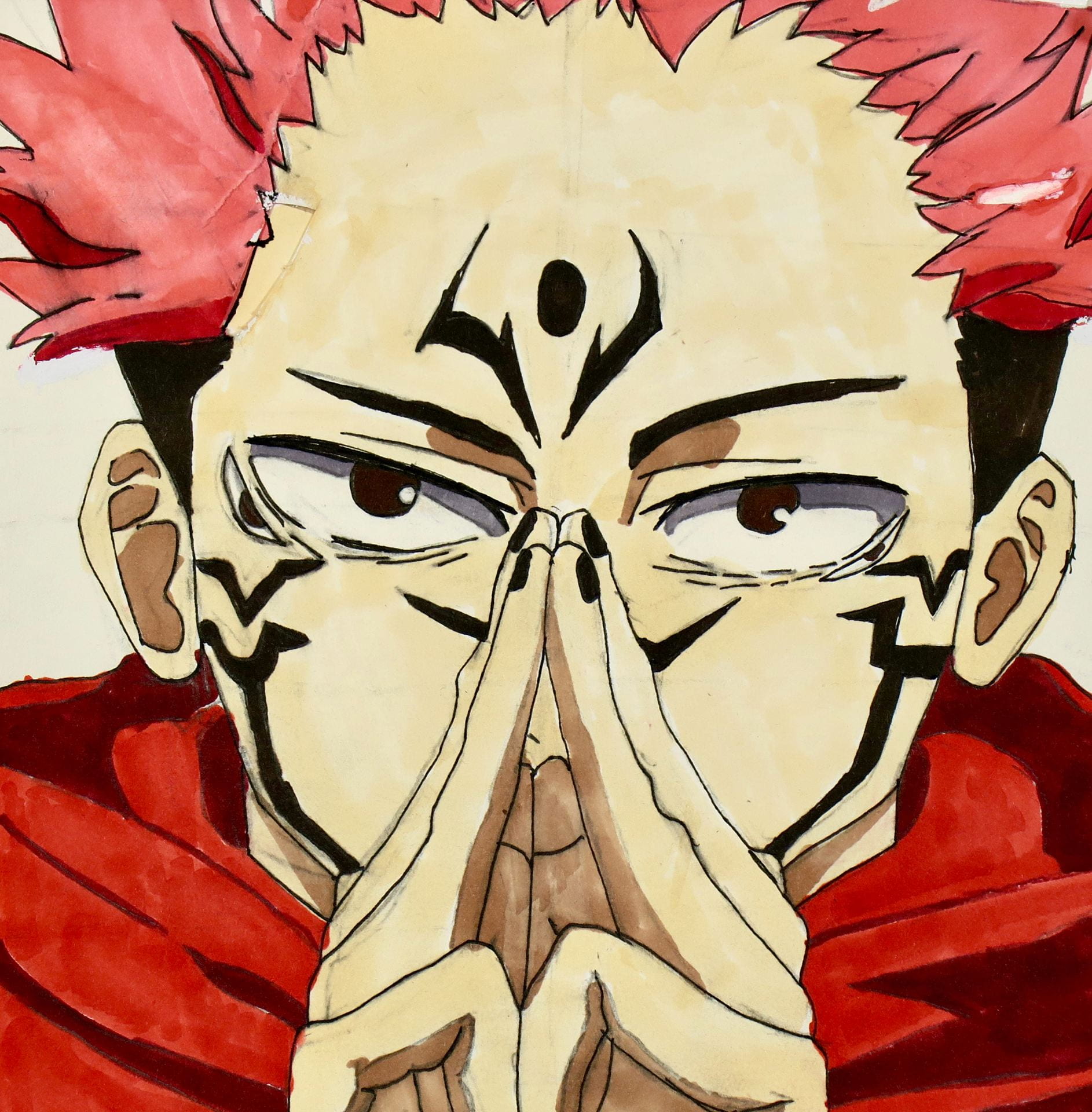

Keira P. ’26

Unfinished

by: Jonah G. ’27

It winter-spread across a barren page,

the foundering island left forlorn, alone.

And then another comes to make a mound

of clashing changing consonantal sound

and striving to find the words to string to words

with no sign but to make the author heard.

Fountain spelling line that follows line

and coming, follow line for one design.

But it is pain to find a followed path

and after pain comes fierce red, fiery wrath.

But string then comes to bind all entered noise

to show that I convince you; I have poise.

And from the fountain’s splashing in the sea,

its voices sing across now mournfully.

A final purpose comes through fluffy rhymes

repeated oh, so many, many times.

The fountain dries; the red sparks then release

as writing cools to well-known final peace.

I’ll start again; this was a golden try.

But to you, poem, I now must say–

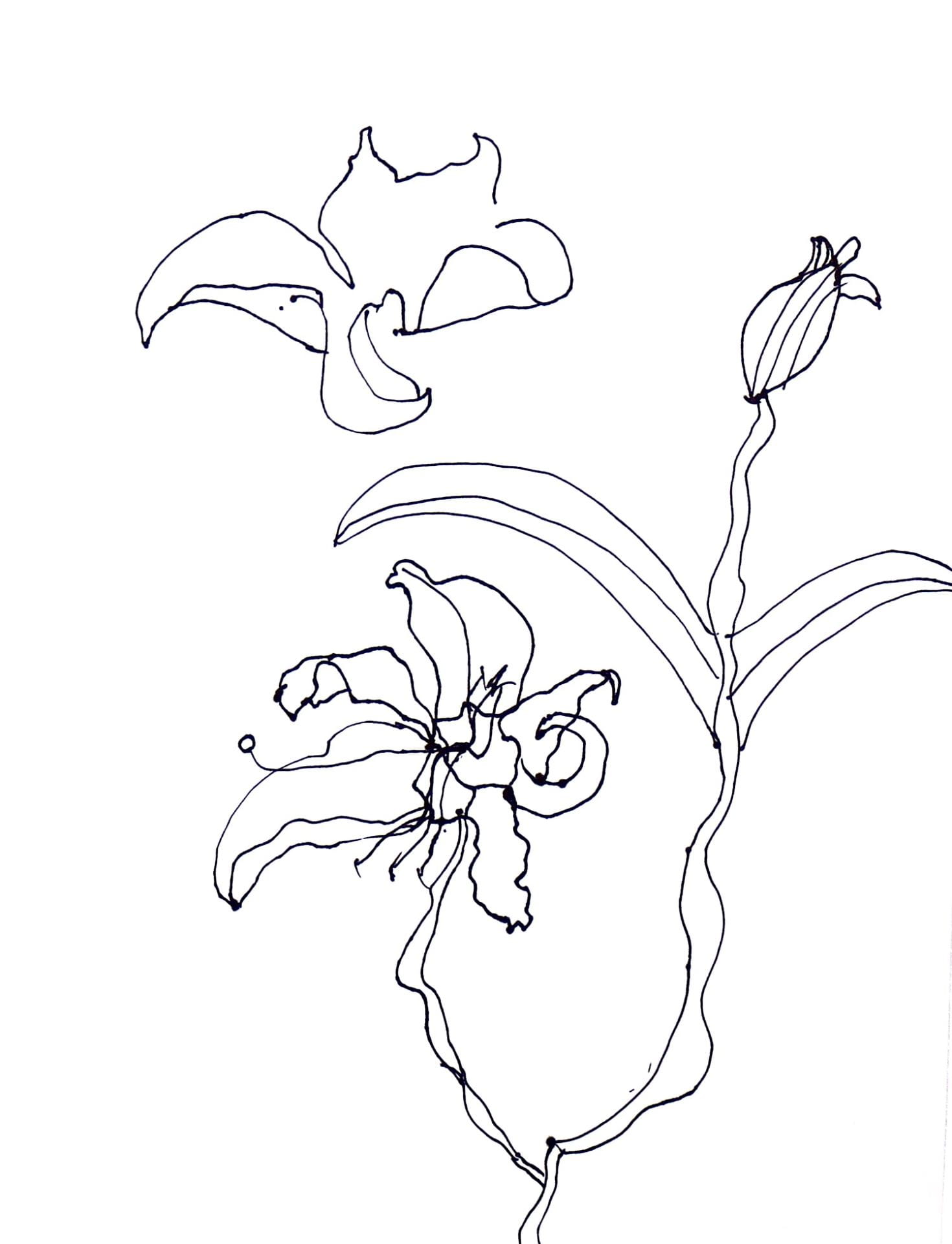

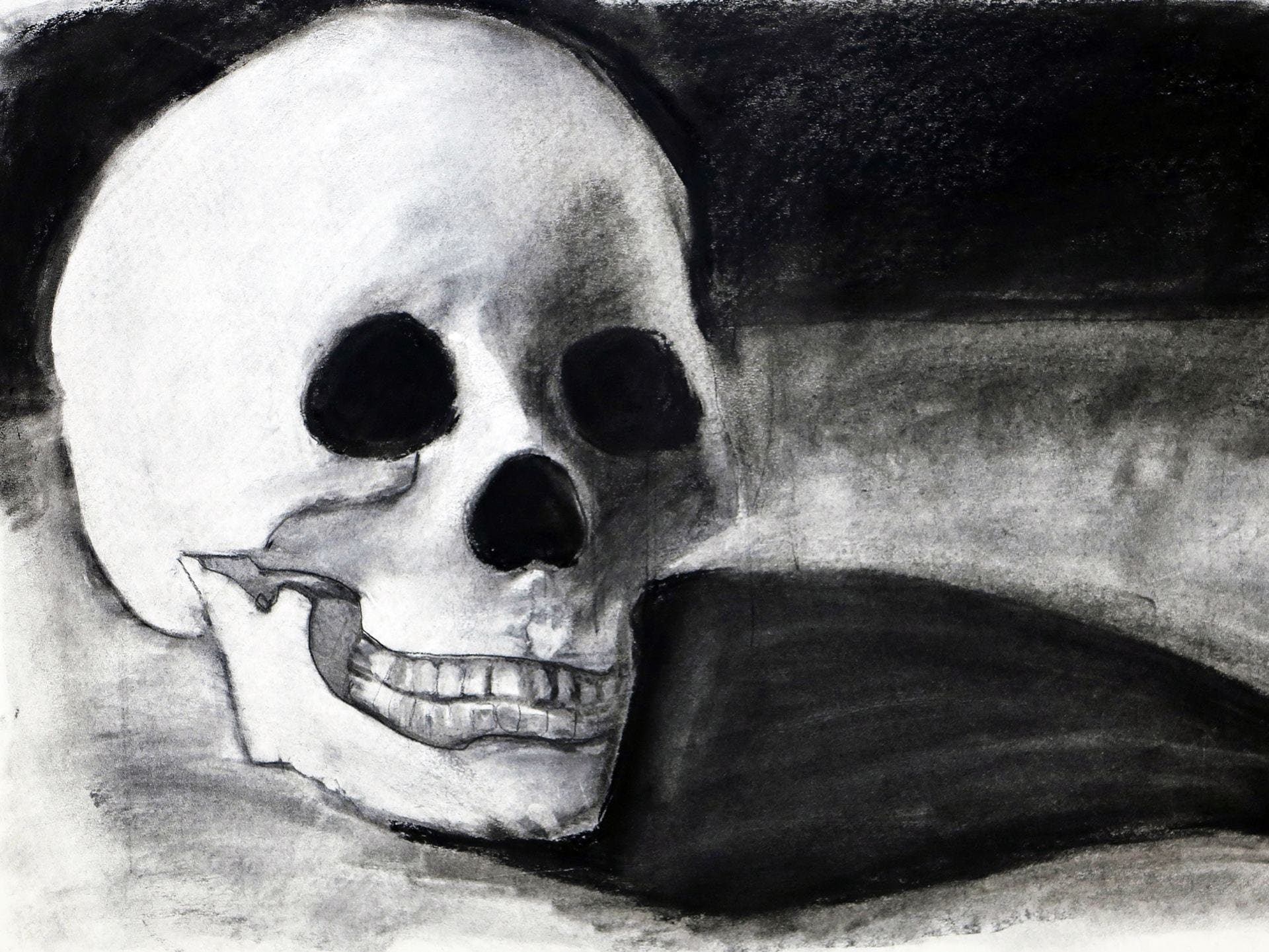

Ali B. ’29

Color

by: Juno Y. ’26

Red.

The first time I saw her, I wasn’t sure she was real. The only thing I saw when I stumbled in the room was her. Auburn hair haloed her face, cascading down in perfect, shining waves that I could never accomplish, and my heart stuttered.

Orange.

Anyone would be stupid to not fall for her. She had this energy that unfurled in the air around her, an eternal wind that flowed through her hair. When she laughed, the fire flickered, and the pumpkin spice leaves spun and spun around her; she was the center, and I burned for her.

Yellow.

Yes. Yes yes yes. Somewhere in our language of shy glances and coy smiles, she knew. Of course she did. We spun in the sunshine, laughter ringing through the halls. My life brightened, days turning into glowing swirls of bliss and smooth honey, because I was with her.

Green.

Doubt crept in, crowding our happiness from both sides. Eyes narrowed, smiles sharpened. A fog descended. I couldn’t put a finger on how it happened, or when, but over the span of several months, a poison—radioactive green—dripped into our minds.

Blue.

Why? I don’t know. I wish I did. That wouldn’t matter. So cold. The sky in summer, a bright cornflower, descended into the lonely off-black of the edge of space. The sharp sapphire of her eyes when she told me, welling up with tears. So, so, cold.

Purple.

It was the feeling of something long gone. The whole world tipped upside down, leaving me crying on the ceiling. It was twilight when she left. She was still beautiful, bathed in the violets of the dying sun, crushing the remnants of our relationship. I watched it fracture, a thousand shards of glass revealing us in a thousand shades of color.

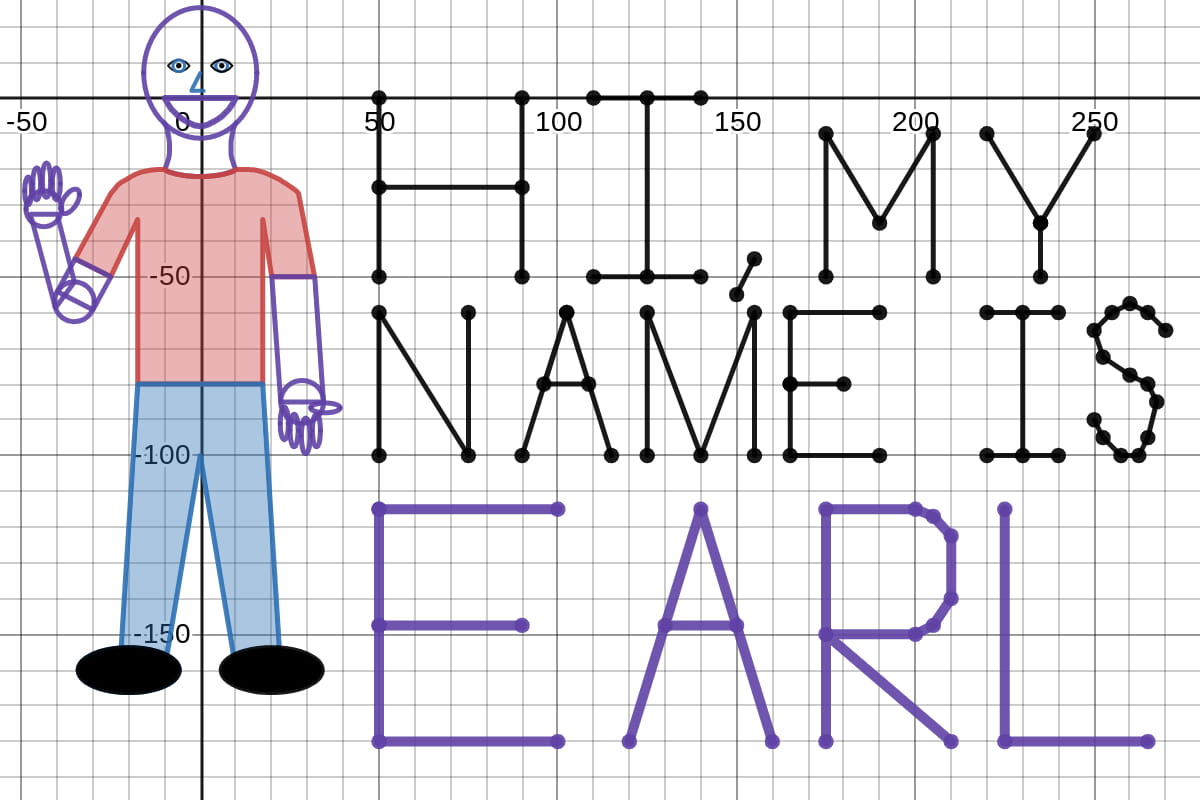

Bode C. ’26