Essay by Ben I. ’26

Introduction

An orphan, a senator, a general, a lawyer, a vice president, a father, a husband, a leader, a traitor, and a murderer. A man who had so much to lose and lived his life without taking a risk. When he did, he ruined his legacy, was known to be the murderer of Alexander Hamilton and a traitor to his country. A man who did whatever it took to get to the top only to lose it all. This man was Aaron Burr.

Young Life

Aaron Burr Jr. was born on February 6th, 1756 in Newark, New Jersey. His parents were Aaron Burr Sr., who was the second president of the College of New Jersey, now known as Princeton University, and Esther Edwards Burr, his mother. He had an older sister named Sarah (“Sally”) Burr.

Burr’s father died in 1757 while being the president of Princeton College. Burr’s grandfather, Jonathan Edwards, was after Burr’s father as president, and he and his wife began living with Burr and his mother in December 1757. Burr’s grandfather died in March 1758 and Burr’s mother and grandmother also died within the year, leaving Burr and his sister orphans when he was two years old. Aaron and Sally were then taken care of by the William Shippen family in Philadelphia. In 1759, the children were given to their 21-year-old uncle Timothy Edwards. The next year, Edwards married Rhoda Ogden and moved to Elizabeth, New Jersey. Burr had a very terrible relationship with his uncle, who was often physically abusive. As a child, he tried to run away from home several times.

At the age of 13, he was accepted into Princeton and he studied there till he was 19. He met Hamilton there as well, but Hamilton was not accepted and the bursar of the school laughed and called him an idiot, Hamilton’s response was punching him in the face. The two became friends and would sometimes meet during the war but spit when they split parties. When he was 19 he decided to move to Connecticut to study law with his brother-in-law. But in 1775 he heard the news of the revolutionary war and put a hold to his studies to join the Continental Army.

Burr in the Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War Burr took part in Benedict Arnold’s expedition to Quebec, which was more than 300 miles through the frontier of Maine. Arnold was impressed by Burr’s “great spirit and resolution” during the long journey and sent him up the Saint Lawrence River to contact General Richard Montgomery, who had taken Montreal and escort the general to Quebec. Montgomery then promoted Burr to captain and made him an aide-de-camp (fancy word for secretary), Washington did also except for Hamilton. Burr did an amazing job during the Battle of Quebec on December 31, 1775, where he tried to recover Montgomery’s corpse after he had been shot in the neck.

In the spring of 1776, Burr’s step brother Matthias Ogden helped him to get a position with George Washington’s staff in Manhattan, but he quit on June 26 to be able to fight. General Israel Putnam took Burr under his wing, and Burr saved an entire brigade from capture after the British landing in Manhattan by his idea to retreat from lower Manhattan to Harlem. Washington failed to commend Burr for his idea in the next day’s General Orders, which was the fastest way to obtain a promotion. Burr was already a nationally known hero, but he never received a commendation. He also tried to be accepted as Washington’s secretary but was replaced by Alexander Hamilton. According to Ogden, he was extremely angry by the incident, which may have led to the odd relationship between him and Washington. Burr still defended Washington’s decision to evacuate New York. It was not until the 1790s that the two men decided to be on opposite sides in politics.

Burr was placed with a regiment in 1777 where he was placed in Westchester County, New York. 2 years later he became ill and in March 1779 he resigned from the Continental Army and went to Connecticut to help until 1781 when the war was finished.

Marriage to Theodosia Bartow Prevost

Burr met Theodosia in August 1778 while she was married to Jaques Marcus Prevost, a British officer placed in Georgia. While Prevost was gone, Burr would visit Theodosia regularly. The visits began starting gossip and by 1780 they were open lovers. But, in December 1781 Theodosia learned that Prevost died from yellow fever while in Jamaica. She and Burr got married in 1782 and moved into a house on Wall Street.

Burr’s Children

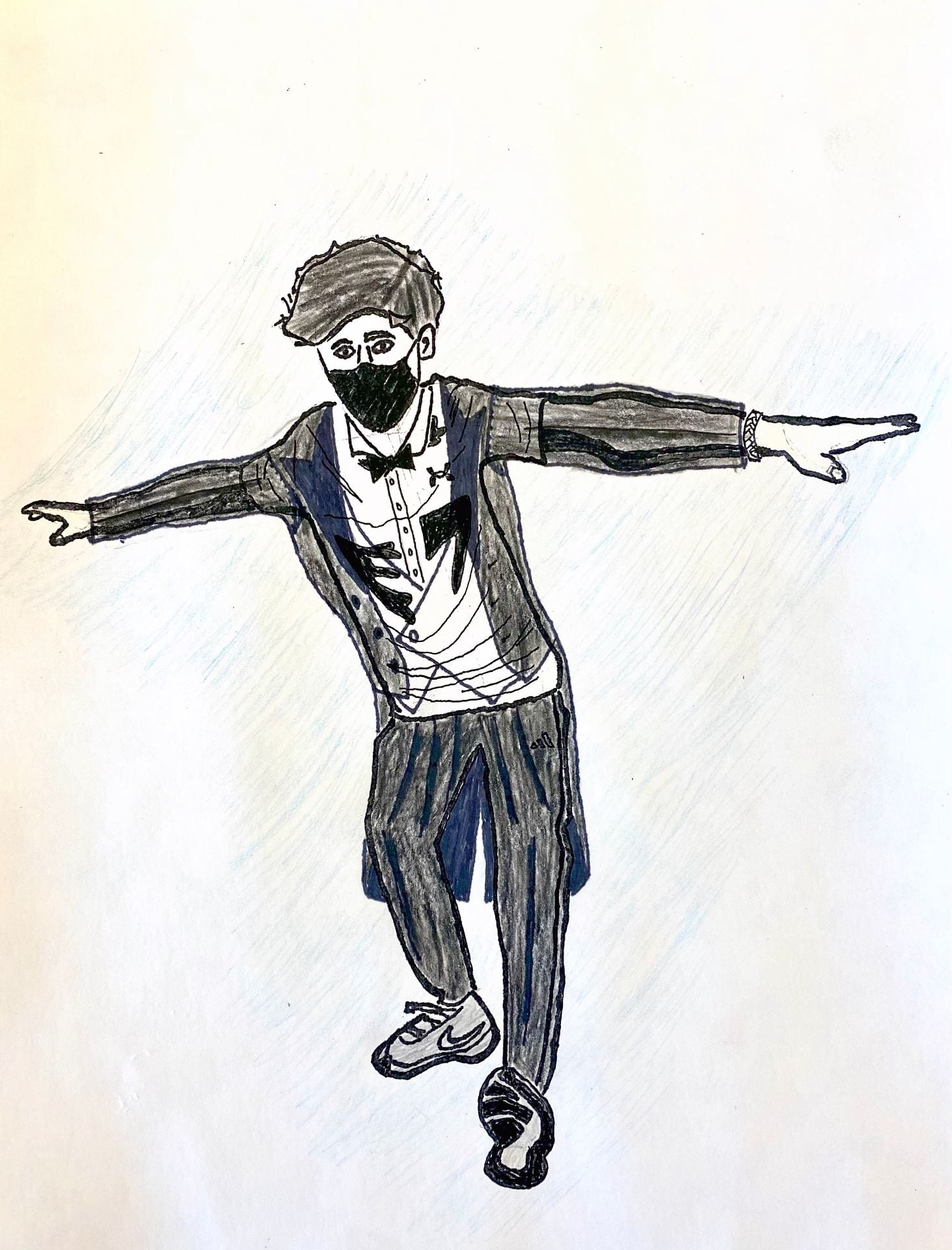

Aaron Burr had many children with different mothers, and he kept some in hiding and did not even know about the other children. Which makes it so hard to count all of them. We do know that he was the father of Theodosia Burr, John Pierre Burr, Louisa Charlotte Burr, and he also fathered Francis Ann and Elizabeth later in his life and acknowledged them by giving them his estate in his will a year before he died. John Pierre Burr and Louisa Charlotte Burr were both the children of one of Theodosia’s servents and were born during the marriage of Aaron Burr and Theodosia. He also adopted Aaron Colombus Burr and Charles Burdett and was the stepfather to Augustine James Frederick Prevost and John Bartow Prevost. He also served as the legal guardian of Nathalie de Lage de Volude and John Vanderlyn who painted the painting you see on the cover.

Burr After the war

Burr served in the New York State Assembly from 1784 to 1785. He became seriously involved in politics in 1789 when George Clinton put him as New York State Attorney General. In 1791, he was elected by the legislature as a Senator from New York, defeating Philip Schuyler, Alexander Hamilton’s father in law. He was in the Senate until 1797. He ran for president in 1796 and came in fourth. Burr was elected to the New York State Assembly in 1798 and did it till 1799. During this time, he joined with the Holland Land Company in making a law to permit aliens to hold and convey lands. In September 1799, Burr fought a duel with John Barker Church, whose wife was Angelica Schuyler Church and was the sister of Hamilton’s wife Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton. John Barker Church had accused Burr of taking a bribe from the Holland Company for his political influence. Burr and Church shot at each other and missed, and afterward, Church realized that he was wrong to have accused Burr without proof. Burr accepted this as an apology, and they shook hands and ended the argument. In 1799 he also founded Bank of The Manhattan Company. Burr was a Democratic-Republican but was very close to the Federalist party.

The election of 1800

Burr ran for president in 1800. He gained a place on the Democratic-Republican presidential ticket in the 1800 election with Jefferson. Though Jefferson and Burr won New York, he and Burr tied for being president, with 73 electoral votes each. Members of the Democratic-Republican Party intended that Jefferson should be president and Burr vice president, but the tied vote meant that the final choice was made by the House of Representatives, with each of the 16 states having one vote, and nine votes needed for election.

Publicly, Burr remained quiet and refused to surrender the presidency to Jefferson, the great enemy of the Federalists. Rumors came that Burr and a bunch of Federalists were encouraging Republican representatives to vote for him, blocking Jefferson’s election in the House. However, solid evidence of such a conspiracy was lacking, and historians generally gave Burr the benefit of the doubt. In 2011, however, historian Thomas Baker discovered a previously unknown letter from William P. Van Ness to Edward Livingston, two leading Democratic-Republicans in New York that proved the theory. Van Ness was very close to Burr—serving as his second in the next duel with Hamilton. As a leading Democratic-Republican, Van Ness secretly supported the Federalist plan to elect Burr as president and tried to get Livingston to join. Livingston agreed at first, then reversed himself. Baker argues that Burr probably supported the Van Ness plan. The attempt did not work, due partly to Livingston’s reversal, but more to Hamilton’s opposition to Burr and how in a dinner with the House of Representatives he openly said Burr was “a dangerous man and one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government”. Jefferson was elected president, and Burr vice president.

Hamilton vs. Burr duel

Burr, very angry at Hamilton, sent a letter talking about how Hamilton had been disrespectful and the two exchanged letters until Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel. Dueling had been outlawed in New York in which the sentence for dueling was death. It was illegal in New Jersey as well, but the consequences were less severe. On July 11, 1804, the old friends now enemies met outside Weehawken, New Jersey, at the same spot where Hamilton’s oldest son had died in a duel just three years before. Burr fired and Hamilton did as well, but in the sky and Hamilton was mortally wounded by a shot just above the hip. He died with his loved ones in New York the next day. Burr was charged with multiple crimes, including murder, in New York and New Jersey. He ran away to South Carolina, where his daughter lived with her family, but soon returned to Philadelphia and then to Washington to complete his term as vice president. He avoided New York and New Jersey for a time, but all the charges against him were eventually dropped. The reason it wasn’t just New Jersey was because although Hamilton was shot in New Jersey, he died in New York.

Conclusion

Most people believe this is the end of Burr’s story but there is so much more about his life. He lived another 30 years after the duel with Hamilton, and I will tell that story in my second essay The Life of Aaron Burr: Succeeding Hamilton.

Parrot & Idabelle

by: Fiona P. ’26

Idabelle Nibley had spent her twenty-one years ignorant of the world around her.

Which most certainly bothered some people, the doll in the green dress on her shelf to name one.

She called herself Parrot, for she had overheard Idabelle bragging to a friend about the gift her sea-faring father was to bring back to her and thought the word was simply splendid. She had no idea what a Parrot was, of course, but thought that if Mr Nibley had anything to do with it, it had to be perfect.

Idabelle spent exactly three days paying any attention to Parrot. Parrot longed to relive those days that the vain, spoiled girl had spent with her: showing the doll off to her cousins, bringing her to show-and-tell (one of Idabelle’s major accomplishments was always having the best things for Miss Blakely’s show-and-tell), sitting her next to her in the family pew on the Sunday. Parrot grew ecstatic after she went to her first mass, and patiently awaited for the next Sunday to come around and for Idabelle to put on her frilly pink satin frock and put ribbons around her milk chocolate ringlets and then dress Parrot up to match. But, the second Sunday never came, and instead Idabelle showed off her new pink lace parasol to the church. (Yes, Jesus would disapprove of her vanity, her pretentiousness, and really many other things, but she was confident not even He could hold out against her dazzling angelic smiles.)

Parrot’s naïveté entertained the other toys in Idabelle’s room. On the shelf between the windows where she sat, there was a teddy bear and a set of nesting dolls. The nesting dolls had long foreign names with lots of ks and vs and os and as, and were always unstacked, unfortunately for Parrot. They, along with the other nearby toys, would laugh at and taunt Parrot often. However the bear, who called himself Sebastian, had plenty of advice for the heartbroken doll.

Parrot spent her days longingly gazing at Idabelle’s newest craze. She knew, however, that those toys would all soon be retired to their shelves and never fawned over again.

And they all followed in the footsteps of their predecessors to the bookcase which held no books or the shelf between the windows or the desk Idabelle had never sat down at.

At the moment, however, Parrot was in a predicament. Idabelle’s room was being cleaned – not by her, of course, for she didn’t even know how to pick up a mop – but by one of the housemaids to fix up her room before Idabelle’s wedding. Idabelle wanted all her toys to move with her to her new house, and there was a great fuss. Parrot had been removed from her shelf and tossed hap-hazardly face-down on the pink carpet. Her arm was bent underneath her in the most uncomfortable manner and her dress, which was already covered in dust, was getting more and more wrinkled by the minute. She could hear Idabelle prattling above her.

“Put all the dresses in this trunk, here,” Idabelle’s nasally voice demanded to her maid, Augusta. “And make sure the best ones are on top.”

A gentle knock came on the door.“Idabelle,” Mr Nibley said from outside. Parrot heard a hint of sadness in his voice. “Are you almost ready? Your mother and Mr Coombs are awaiting your presence in the carriage.” The door opened and Parrot heard footsteps enter the room.

“Maid, fetch me some tea,” said Idabelle. Augusta scuttled out the door.

“Idabelle, are you almost ready? Please, we must go.”

“Well yes, almost, I wanted to get all my toys before I left. I’m so elated I could nearly faint!”

“Idabelle, are you sure you wish to bring your childhood belongings?”

“Of course, Daddy. Most of them are from you so why do you complain? After all if you didn’t wish for me to have them why would you wish me to be away with them? They will all help make the Coombs estate feel like home.”

“You wish to bring all of the toys?

“Well of course, Daddy.”

“Just this once, Idabelle, I must put my foot down. You cannot bring them all. I’ll give them myself to the poorhouse.”

“No! Daddy, you wouldn’t! Don’t do such a thing!”

Just then, the door burst open and two sets of footsteps bustled in.

“Oh, Idabelle!” gushed one of the newcomers, Mrs Nibley from the sound of it. “I can’t believe my little girl is all grown up! You look lovely, doesn’t she, Mr Coombs? Oh, do step inside. We must have a chat before you head off. The carriage is downstairs, but it can wait a minute. Sally, pour us the tea. Sally! Yes, you. Good. Now. We must speak of the service, oh, it will be so beautiful! I can’t recall all the details.” Mrs Nibley prattled on about the dress, the new house, and the cake for minutes on end before Mr Nibley could remind her they had a carriage to catch.

“Wait!” Idabelle exclaimed. “Daddy, can I take a toy with me? Please?” Parrot could practically hear Mr Nibley’s eyes roll.

“It’s your wedding day, Idabelle, don’t be silly.”

“But Daddy! I want at least one!” whined Idabelle.

“You’re no longer a little girl.” Mr Nibley leaned closer to his daughter and whispered, “This is for your sake, my dear. Hemptonshire is a small town and I don’t want the entire village to think ill of you, your husband included.”

Idabelle tittered. “Oh, you’re so funny, Daddy! Who could ever think ill of me?” She snorted and Parrot imagined that she tossed her plait over her shoulder. Mr Nibley sighed.

“No one, dear.”

“Good. Maid, pack up the toys.”

“Do not pack up the toys!”

“Yes, do! Now! You’re my maid!”

“And I am your father and you will do as I say!”

Poor Augusta just stood there, not knowing who to obey or what to do. Should she stay still and face the wrath of Idabelle, or pack the toys and risk losing her job? Parrot had learned from maids talking in the room that Augusta had seven siblings and an ailing mother. The torn maid decided, after several rather awkward seconds, to stay still. It was, after all, Idabelle’s last day at Westbrook. She could bear Idabelle’s temper for one more day. Perhaps she would be moved to one of Idabelle’s sweet-tempered sisters!

“Good. Idabelle, move along.”

“No! Give! Me! My! Toys!!”

“Absolutely not. I won’t have it.”

“DA-ddy! You’re so horrible! You never let me have any fun!”

“You cannot have the dolls and that is final.”

It was Mrs Nibley who spoke next. “Mr Nibley! For once in your life make your daughter happy! All you’ve done is stop her from having fun. Now now, Idabelle, take this one. She has such nice, pretty curls and blue eyes just like you.” Parrot gleefully watched the rug shrink as she was lifted into the air and handed to the grumpy girl.

“Thank you, Mother.” Idabelle blew a raspberry at her father. Parrot felt a soaring rush of ecstasy. Unfortunately, Parrot thought for a moment that Idabelle was actually going to care for her again.

As the parents and Mr Coombs left the bedroom, Idabelle stopped.

“Where are these doll’s clothes?” she demanded of Augusta.“Over there, ma’am.” Idabelle snatched up a lacy white dress and took Parrot’s old, green one off. She stuffed the bridal-like gown over Parrot’s head and slipped on white tights and baby pink satin flats.

“Perfect!” Idabelle danced down the downstairs leisurely, flitting past the portraits of her ancestors and running her fingers along the antique canvases. For Parrot, seeing the mansion’s entry hall brought back all sorts of memories. She recalled how Mr Nibley had scan the shelves of the toy store in London for a new addition to his daughter’s collection. Parrot, or Sylvia, as the tag on the box she came in read, was the perfect choice for his daughter. She was dressed in the latest fashion and made by the fanciest toymaker in all of England. She had heard, on her first day, a few dolls talking of the fate of a previous toy, Colette: after it was out of fashion, it was put into the waste bin and incinerated. She had just begun to think that Colette’s fate might be her own when Mr Nibley had saved her.

She remembered how those first few days at Westbrook had shown her about the world beyond the shop, and how she watched with jealousy and heartbreak as Idabelle unwrapped a silk-covered box and discovered a new pair of leather boots the fourth day.

Idabelle flitted out the door with Parrot in her arms and joined Mr Coombs, Mr Coombs’ parents, and her parents in the open carriage.

“Oh, hello, Edward!” Idabelle tittered. “Oh, how thrilling this day is! Now Edward, this is Sylvia.” Idabelle pointed at Parrot. “Make room so she can sit, that’s a dear.” The driver cracked his whip and took off to the church.

Idabelle stepped out of her carriage and all the people who had come to see Idabelle’s wedding stood in front of the church and clapped.

“Ladies and gentlemen, I present Lord Edward Coombs and Lady Idabelle Nibley!” The crowd clapped.

“Careful of the mud, dear,” said Mr Coombs.

“Carry me, dear.” Idabelle was hoisted up unenthusiastically and they set across the mud. Suddenly, Parrot slipped from her grasp and tumbled down, down, down and into the mud.

The dirty water soaked chillingly through her satin slippers. The mud caked onto her skin and stuck in her joints, rendering her unmovable. Her dress was torn on Idabelle’s ring and seeped into the fine lace. Only half her body was saved from submergence, her fragile sterling ear-rings clanking against pebbles among the soupy sludge. “Save me, Idabelle!” thought Parrot.

But Idabelle only continued inside, ignorant, and left Parrot lying face up in a pile of horse manure and muck. Parrot felt as if she could cry.

“That stupid, simple-minded girl,” thought Parrot. “She’s all decked up in a nice white dress while I lie here in the mud with nothing I can do for myself! What did I do to deserve this? Nothing, I tell you, absolutely nothing. All I did was sit on that shelf for eight years and wait, wait for something to happen! I waited and I waited for days but nothing ever came. What was I looking for in the first place? An escape, likely. Well, I escaped, that’s for sure, but now I’m here and I might as well be back on the shelf-between-the-windows! Even Sebastian and those nasty dolls are luckier than I, sitting nice and clean in that trunk of theirs to go the poor. Oh, how silly I was to think Idabelle liked me again. She got me in her trap again, didn’t she. Why does such a horrible girl get to be a human when I’m stuck here in the lace dress becoming a mud pie and I can’t do anything about it! Stupid limbs, stupid horse-hair ringlets, stupid glass eyes.”

Just as Parrot’s despair was about to consume her, she had a new problem to deal with.

A gang of young boys came down the road.

“Look here, Johnny!” said a lad about eleven, with scruffy blond hair and eager brown eyes. Johnny, the oldest, turned and looked at what he was pointing to. “A little doll!” Johnny squinted at Parrot.

“What’re ya trying to get at, Tom?” asked Johnny.

“Let’s tease my sister with it, shall we?” The boys agreed and Tom, the youngest and new in town, picked up Parrot.

“What, oh what, has become of me?” she thought desperately as the boys carried her to town. They stopped on the cobblestone road and Idabelle caught a glimpse of the small, two-story white stone house Tom must have lived in.

“Hey Charlotte!” called Tom to his sister. “Come down here!” A little girl of eight in a light blue gingham frock peeked out the front door.

“What is it?” She asked tentatively,.

“Look here!” Tom tossed the doll high into the air and it spun down into to Tom’s hand. Parrot felt her stomach go queasy. He threw her up again and again until the little girl’s face was wrought with anger.

“Give her here!” Charlotte ran to the boys and pushed Tom, making another grab at the doll. Tom threw it to one of his buddies, who promptly tossed it to the next boy. The world spun around as Parrot was thrown from boy to boy and her stomach churned. Charlotte’s eyes brimmed with tears and when Parrot was thrown back to Tom, she pushed him and snatched up the doll. The boys laughed behind her as she stomped back inside.

She set Parrot down on the oak kitchen table and furrowed her brow. “Look at you, poor thing,” she said to Parrot. “Let’s clean you up.” Parrot was soaked, scrubbed, and dressed. An odd, new feeling warmed in her chest as Charlotte carefully tended to her.

Charlotte played with Parrot every day and never ignored her. Only once, as Charlotte was chatting to her, did she hear of Idabelle. It had happened that the ignorant girl fell sick and was rushed out of Hemptonshire to go to the sea.